Nigerian troops accused in killings

Villagers say soldiers

shot 7 protestors

at Shell oil rig

Craig Timberg

10 December 2004

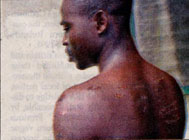

Stanley Pakemi: Soldiers arrested him during a protest

Stanley Pakemi: Soldiers arrested him during a protest

against the Shell Oil Company and repeatedly

whipped him with wires.

Ojobo, Nigeria: There are seven freshly dug graves in this Niger Delta village. Local leaders say they contain the remains of protesters who died violently last month when they attempted to mount a protest at an oil rig operated by the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria, the region's largest oil firm.

According to the villagers, more than 100 men traveled by motorboat down a creek toward the rig, where they gathered on a barge and sent leaders to demand a meeting with Company officials to discuss languishing development projects.

Instead, they said, army troops appeared in three boats and opened fire on the barge.

Stanley Pakemi, a 28-year-old survivor, said the soldiers detained him for more than two days and whipped him repeatedly with wires. Now, like many Delta residents, he said he is ready to see Shell and the other oil companies leave. "If this is the way they are going to treat us, I don't want them here." he said.

Spokesmen for Shell and the Nigerian army disputed these accounts, saying they knew of no deaths in the November 20 incident. Simon Buerk, a Shell spokesman, said that violence broke out after one the protesters attempted to disarm a soldier and that 17 people were injured in the clash. He said the Company was reopening an investigation into the incident.

What is beyond dispute, however, is the volatility of the Delta region as Nigerians scramble for a share of oil wealth. In villages across the region, frustration at the persistence of poverty within sight of vast wealth is boiling over, leading to bloody clashes, calls for revolution and more than 1000 deaths a year, according to a report prepared for Shell by consultants.

While surging oil prices have swollen government accounts and business profits in Nigeria, the boom has offered few benefits to people living near the wells while damaging the environment and giving rise to violent struggles among competing groups, say residents and watchdog groups.

Ojobo, located amid oil reserves worth many milions of dollars, has neither paved roads nor power. Toilets are latrines built over the creek, and a community well, built by an oil company, produces no water.

Nigeria is the United States' fifth-largest supplier of foreign oil and the largest oil producer in Africa. The industry generates billions of dollars a year for the Nigerian government, which owns all oil rights in the country and has a majoritiy interest in every oil company operating in the country.

Yet there is little evidence that prosperity is reaching the people of the Niger Delta. Inhabitants of villages throughout the vast region of mangrove swamps and twisting waterways struggle to survive at subsistence levels.

Violence is increasing in a region already awash in weapons and riven by tribal tensions. Militias controlled by community leaders attack one another with often deadly results, and assaults on civilians by the army and police are common, according to human rights groups and residents.

Armed gangs also thrive, stealing oil straight from the Delta's pipelines each day. Less sophisticated criminals cut into the pipelines with hacksaws, creating cleanup work for local contractors. Of the 221 oil spills reported by Shell last year, two-thirds were the result of sabotage, the company said.

The Shell consultants' report said conditions were deteriorating so rapidly that the company might have to move all of its operations offshore by 2009. The report, by WAC Global Services, concluded that Shell was in part responsible for the rampant violence and criminality in the Niger Delta.

Shell officials dispute that conclusion, saying they remain welcome

in the region and intend to stay. Yet they acknowledge a legacy of

flawed efforts to promote community development, despite investments

that reached $84 million last year alone. "We are oil and gas people.

We are not really strong in development," said Basil Omiyi, the top

Shell official in Nigera. He added, "If the government was doing their

role properly, we would have to do much, much, much less."

Reprinted from the San Francisco Chronicle 10 December

2004

Back to Articles and Reprints

1800 Cedar Street

Berkeley, California 94703

Telephone: (510) 841-4106

noon til six, Monday thru Saturday

Pacific Time

HOME